Has it been 100 years already? Why yes, yes it has. What was Arnold Rönnebeck creating 100 years ago? Where was he? What was he doing?

In this space over the next several years we will be celebrating what Arnold Rönnebeck was creating 100 years ago, beginning in 1921, found at the bottom of this page.

1924

“Why not modern art? Ask a lady, Why a modern hat? Why bobbed hair? Why the boyish tailormade? Why drive your car instead of walking? The lady might answer, ‘Because I live in 1924!’ And so I think that is the reason why we have modern art. We live in 1924, not in 1800, and the art of today must reflect the period.”

Arnold Rönnebeck in the Washington Herald June 1, 1924

The art of 1924. That is what Arnold was after during his first full year living in the United States. “The Sioux, Skyscrapers, Jazz and Other Possibilities” was the title of a lecture Arnold gave at the Art Center in Washington, DC in Spring 1924. It could also be the theme of this active and pivotal year for him. He immersed himself in American culture but interpreted and expressed it through the lens of his European sensibilities.

Arnold began the year still living in Glendale, Maryland with the Pinch family, as well as working, exhibiting and lecturing in Washington DC. The February 2, 1924 issue of Art News wrote that “he has taken a studio at The Art Center, where he is exhibiting”. That is logical since Glendale was some distance from Washington DC. Between February 3-March 2, 1924, Arnold exhibited in the Corcoran Gallery’s exhibition of the Society of Washington Artists, Washington, DC. Included in this show were his Dancing Youths aka Arcadia plaster relief panels, one of his portrait heads of Marsden Hartley (most likely the 1912 bronze) and one of his 1920-21 Positano lithographs. During these early months of Arnold’s life in the U.S., he was exhibiting existing works that he had brought with him from Germany.

In April he gave a weekly series of lectures on modern art in Europe and America at the Art Center in Washington, DC. Titles of the lectures were “Oil Scandals in Paris”, “The Sioux, the Skyscrapers, Jazz and Other Possibilities” and “The Secret of Pygmalion”. In the June interview he gave to the Washington Herald he discussed what he said was his personal “secret of Pygmalion”:

“I noticed that nature was grand and powerful and the effect of my work was small. What was the reason for this strange difference? In my studio I had a few plaster casts from antique busts. I put my model between my work and one of these casts. And what did I see? The antique work was simplified, quasi-enlarged, it had big, simple planes, which my work lacked. There lay the secret and I had made a great discovery. The important thing was to find the essential and significant planes”.

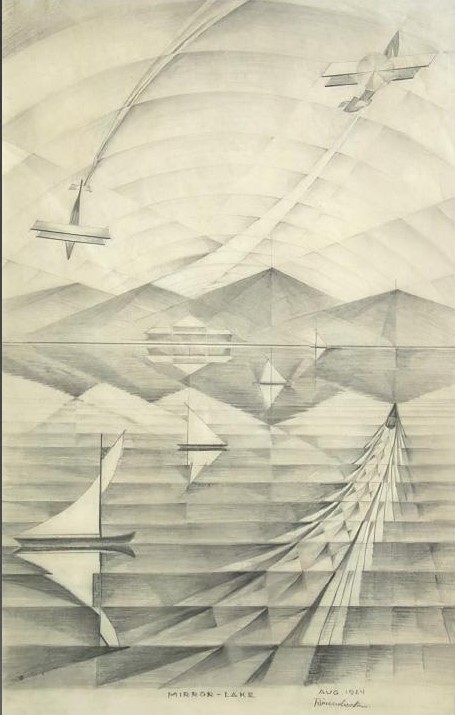

We would see the expression of this approach in several of Arnold’s works such as his brass Dancer (1921), brass Mask (1923) Mirror Lake pencil drawing (1924), and London Wedding bronze (1924).

In August and September Arnold ventured out of the city to Lake Placid, New York, specifically Mirror Lake. He told Stieglitz in an August 7th letter that it was because of the “Most charming people, and quite some of the 291 spirit. They asked me to come here – – out of mere belief in me”. We wish we knew who these charming people were, how and where he met them. He added that he was “giving lessons in French, German and Italian conversation” to pay for his accommodation at the Lantern Book Shop. He wrote that he has “a lovely room overlooking Mirror Lake, which in the evening reflects the Club all lined with electric bulbs, in order to not let you forget Broadway in the midst of the old Iroquois hunting grounds.” Arnold’s 1924 pencil drawing, Mirror Lake, displays this vitality.

One known portrait sculpture executed during his time in Lake Placid was a portrait head/mask of a young man named Everett Marcy. His name and the photographs of him shown here (and the others in Arnold’s archives at AAA) is the totality of the information we have at present. While unconfirmed, it is possible that Mr. Marcy may have been the grandnephew of the former governor of New York, William Learned Marcy, after whom the nearby Mount Marcy was named. He would have been about 20 years old in 1924. There was also an Everett Marcy who had a relationship with Mabel Dodge Luhan between 1925-1928 and who was a Broadway writer in the 1930s and 40s. Not sure if they are one and the same. From the Mirror Lake photos in Arnold’s material at the Archives of American Art, when he wasn’t working, Arnold was socializing with his new friends, exploring the hiking trails in the Adirondacks and learning about his newly adopted country, which included attending the Iroquois Fire Council ceremony at the Lake Placid Club.

Following his Lake Placid stay, Arnold spent the second week of October in Lake George with Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe at Stieglitz’s summer residence, The Hill. Amidst the congenial meals on the porch there was a hive of artistic and social activity during that week. Notably, Arnold took some snapshots of Stieglitz photographing O’Keeffe. These photos uniquely document Stieglitz’s and O’Keeffe’s working process in the creation of their ongoing portrait series. The original snapshots are in the Rönnebeck papers at the Archives of American Art. For detailed information about Arnold’s October 1924 photographs of Stieglitz and O’Keeffe, please see the article by Dr. Betsy Fahlman entitled Arnold Rönnebeck and Alfred Stieglitz Remembering the Hill in History of Photography, Alfred Stieglitz 1864-1946, Winter 1996.

Georgia’s sister, Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe (1889-1961), a nurse by profession, but also a talented artist, was at the Hill during Arnold’s stay. There may have been a brief romance between Arnold and Ida, but it did not end well. In a letter dated November 22, 1924 at the Beinecke from Ida to Stieglitz, she wrote, in part:

“Arnold Rönnebeck is DEAD! My great big, wonderful man who told me about the stars, the northern lights, the American Indians, war – – he knows about everything that has interested me from my earliest recollections. There will never be another Rönnebeck for me. . . . Mr. Rönnebeck is focused. All set and focused on the dollar. I have no dollars! You say all is for the best and I hope it is.”

Included in Arnold’s snapshots of his stay at Lake George is a photo of Ida, Georgia, Stieglitz sitting around a table on the porch in midday. The Beinecke has a photo taken by Stieglitz that shows Arnold at the table, but it is too badly deteriorated to display.

Arnold and Alfred Stieglitz corresponded frequently between 1919 and 1945. Stieglitz was an immense help to Arnold particularly at the beginning of his career in the United States. Stieglitz introduced Arnold to Erhard Weyhe and Carl Zigrosser of the Weyhe Gallery, with whom Arnold would continue to work well into the 1940s. In 1925, Arnold contributed an essay for Stieglitz’s Seven Americans show at the Anderson Gallery.

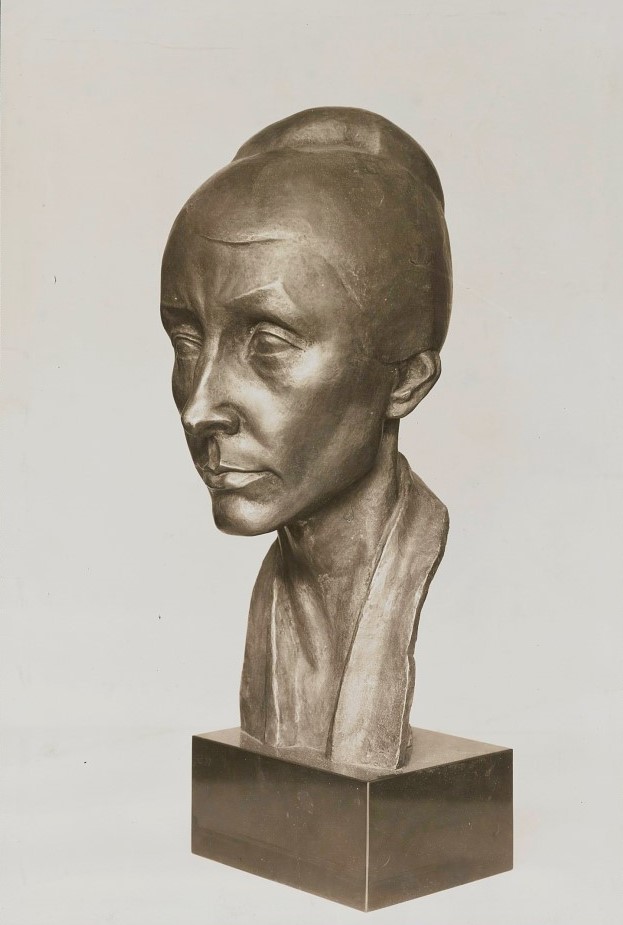

Arnold executed the terra cotta portrait head of Georgia O’Keeffe in 1924. It is difficult, okay, impossible, to imagine that she sat for it. No portrait photographs of O’Keeffe have been found in Arnold’s archives. He could have worked from his snapshots he took at the Hill or perhaps he executed the piece from memory. However he did it, it is a lovely and strong likeness of Georgia. Shortly after its creation, the O’Keeffe portrait was cast in bronze. It was exhibited in Arnold’s 1925 Weyhe Gallery show and traveled to San Diego and Los Angeles for exhibitions. It was also exhibited at the Whitney Studio Club in 1928. On May 13, 1930, Arnold wrote to Stieglitz that he had just sold the O’Keeffe portrait for $1,000 to Delos Chappell, a Denver area businessman. Arnold offered to reimburse Stieglitz for the casting. This was Stieglitz’s May 15, 1930 response:

“when you write about my having paid for the casting of the head and that I had bought a Hartley from you – – I must smile – – for really I had forgotten completely about those “transactions”. Now please forget all about that damned cash. You owe me nothing. You keep the Hartley. It is yours. I never intended it to be anything but yours. And as for the casting of the head I have no idea what was the outlay. So please, consider all of the thousand yours. I’m glad it has worked out as it has. I am poorer by much than a year ago – – and so is O’Keeffe – – but we are better off in a way than when these few dollars were given you to help you on your feet, so the money is really not needed by us – – And you can use it.”

The O’Keeffe portrait bronze is currently owned by Denver University.

In an October 15, 1924 letter to Stieglitz, written while staying at the Hotel Brevoort in Greenwich Village, he described the arrival of the Zeppelin Airship USS Los Angeles ZR3 over New York City. It left Germany on October 12, and in the early morning on October 15, passed over Manhattan, and landed shortly thereafter in New Jersey.

“The enormous silverfish this morning was a most wonderful sight. Shortly after 8 I heard the well-remembered humming of its engines and one side shaved, the other white with lather, I stood on the roof of the above-mentioned hotel and watched the air-leviathan circle the city. There were the French pastry chef and the garcons with me. One had been in London when for the first he heard the same noise . . . It was really very thrilling. Hope it does Germany good. At noon the picture was in the papers: ZR3 above the foreshadowed point of the 10-cent-tower.”

Arnold had wanted to live in New York City since his 1923 U.S. arrival. By mid-October, he moved to a rooming house at 61 Washington Square also in Greenwich Village. His room, for which he paid $10 per week, overlooked the square, had big window with north light, which he wrote was “just splendid for working”. Perhaps he completed the head of O’Keeffe here since he had the space and light. The rooming house was managed by Madame Catherine Branchard, a Swiss woman, who ran it from 1886 until her death in 1937. Throughout her tenure, she let rooms only to artists and writers, usually before they were well-known (Willa Cather, John Dos Passos, John Sloan to name a few), thus earning the nickname, “House of Genius”. Arnold enjoyed the atmosphere. He remained at this address until at least late summer or early fall 1925. The building was torn down in 1948 following a preservation battle.

In the Washington Herald interview Arnold said, “Jazz is rhythmic chaos, but it expresses more than anything else the immense vitality, the movement, the ‘go’ of the life of today”. Arnold’s works I’m a Little Blackbird and Blackbird #3 created in November 1924 depict this vitality. These works portray Harlem Renaissance and Broadway performer, Florence Mills (1896-1927). Amongst many other productions, she appeared in the show “From Dixie to Broadway”, which opened at the Broadhurst Theatre on October 29, 1924. This was the first all-black musical to play on Broadway and the first performance of the song, “I’m a Little Blackbird, Looking for a Blue Bird”. This song inspired her next show, “Lew Leslie’s Black Birds”, which opened at the Alhambra Theatre in Harlem in 1925. The show subsequently traveled to Paris and London. Mills died of complications from an appendectomy in New York in November 1927.

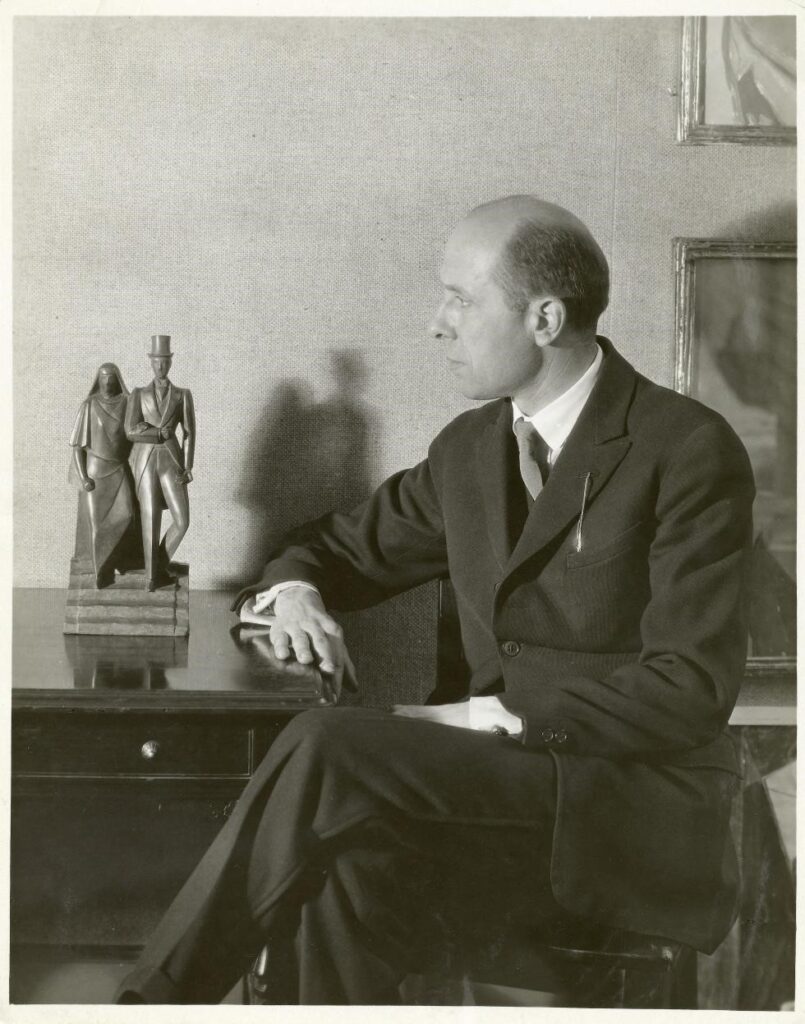

This photo shown here of Arnold with London Wedding was taken in 1924 at Weyhe’s gallery by a photographer from the Therese Bonney Service. London Wedding was executed in terra cotta in 1923 or early 1924. This piece illustrates the “essential and significant planes” approach that he was seeking and discussed in his Secrets of Pygmalion lecture.

In a November 18, 1924 letter To Stieglitz, he wrote that he had “some nice successes” to relay to him. “Yesterday Mrs. Payne Whitney [likely Helen Hay Whitney] walked in at Weyhe and bought two of my things: The London Wedding she ordered in bronze and the Hermaphrodite [1921] she took in plaster. Weyhe is going to have The Wedding cast four times at his own expense, as he thinks we can be sure to sell it at least that often”. We do not know if four were cast in bronze. It is possible only three were cast. We know the location of two London Wedding bronzes. One is in the Art Institute of Chicago and we have confirmed the second one is in a private collection. They were cast at Kunst-Foundry New York, now called Bedi-Makky Art Foundry.

The publication American Modernism at the Art Institute of Chicago, (Yale University Press, 2009) notes that there was also an “American Wedding”, which was exhibited in 1926 at the Brooks Memorial Art Gallery in Memphis Tennessee, but we have not seen photos or other references to this work, so if anyone out there has any information, or even better, some photos, we’d love to hear from you.

Arnold’s first full year in the U.S. was certainly eventful and productive. American culture shifted his perspective and approach to his work. The difference between the economically depressed and war battered Germany that he left behind and the optimism and prosperity he found in his newly adopted home couldn’t be more dramatic.

“My artistic emotion at the ‘phantastic reality of America was beyond all expectation. New York is living cubism. The skyscraper is the symbol of the states, personifying the monumentality of this country, while the express, the locomotive, and the Ford typify the huge distances”.

“Why do American artists seek to paint or sculpt in the traditions of Europe? Impressionism belongs to France. Why should Europeans go back to Egypt or India. America ought to be the country for the creation of art of our time, because here today is already tomorrow”.

Arnold Rönnebeck in the Washington Herald June 1, 1924

Arnold’s tomorrow would be brimming with even more possibilities. In 1925 he would show us his vision of New York as well as other impressions of America, so check back with us sometime in 2025 to learn what 1925 had in store for the artist.

1923

It is an understatement to say that post-war Germany was an extremely difficult place to live. The country was suffering from the consequences of losing the war, and particularly challenging was their obligation to pay war reparations. The economy was absolutely devastated. There were food and fuel shortages. In January 1923 one dollar cost 17,000 marks. By November 1923, one dollar cost 2.2 trillion marks. Not the most conducive atmosphere to pursue the arts. For a sculptor this meant materials were unaffordable.

Economic and post-war emotional challenges aside, Arnold continued to work. We’ve mostly been able to find traditional and modern portraiture, but we presume there was other work as well, we just haven’t discovered it yet. In 1923 he produced four sculpted portraits of Hartley, one of composer George Antheil and a minimalist modern mask/portrait of an “unknown American woman”.

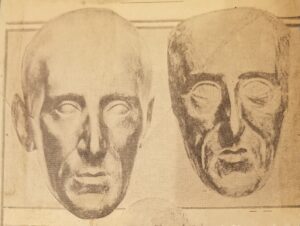

Hartley was still in Berlin and besides sitting for portraits for Arnold, continued to work. He was working in his Kantstrasse apartment and studio on his series of “New Mexico Recollections”, male and female nudes in pastel, and about sixty still lifes. Arnold sculpted four portraits of Hartley in 1923. This is in addition to the bronze portrait of Hartley he executed in 1912 in Paris. Rönnebeck’s 1923 works included two busts in terra cotta and a pair of masks in bronze.

In an undated and unknown newspaper clipping, Arnold discusses the masks.

In the Man, Rönnebeck said, “I attempted to portray the natural man, neither hardened nor softened by the soul’s suffering. Each natural tendency in the head and face runs its course, while in the Soul is shown the spiritual man, his fears and sufferings his hopes and aspirations together with that side which defies explanation, and which men identify with the Infinite”.

Remarkably, Soul foretold quite accurately what Hartley would look like as he aged. The location of the Man mask is currently unknown. We are not aware of a foundry marking, but it was likely cast in Germany. Soul and the terra cotta portrait in which Hartley is wearing a scarf are at the Beinecke and were donated by Arnold’s widow, Louise Ronnebeck, in 1952. The terra cotta portrait with the bow tie is in the Hudson Walker Collection at the Frederick Weisman Museum in Minneapolis, Minnesota. This portrait toured with the Hartley show, American Modern, in 1997-2000 and again in 2005-2008.

Arnold’s brass mask is quite different from his other more traditional portrait sculptures. We are not sure exactly who this piece depicts. Possibly a woman named “Harriett Marsland”, or “Harriett Morsland” or, the safer bet, “unknown American woman”.

In June 1924 the portrait’s sitter is listed as unknown American woman, but by 1925 the work is given a name. There was a Mask of Miss Harriett Marsland listed in the April-May 1925 Weyhe Gallery exhibition catalog and a Mask of Harriet Morsland in the Los Angeles Museum of Art’s June 1926 catalog. A June 1, 1924, Washington Herald review of Arnold’s Art Center Gallery show, states:

“More of an enigma is Rönnebeck’s so-called ‘Portrait Mask’ in polished brass of an unknown American woman, with Sphinx-like face, a strange interpretation, but again the subconscious analyzed as only the true sculptor can do it”.

In an April 1926 review in the San Diego Sun of the Fine Arts Gallery San Diego show, the critic wrote:

“In the life-size bronze, ‘Head of Miss O’Keeffe’ he gives us the literal realistic portrait of his subject, while in the ‘Mask of Harriet Morsland’, done in brass, he shows an abstract rendering of his model with only the absolutely essential and significant forms expressed”.

There was a New York-born Harriett Marsland who arrived in Berlin as a 28-year-old student in 1921, who, judging by her passport photo from the period, looks remarkably similar to the woman depicted in the brass mask. It was likely cast in Germany but given the economic situation we are unsure how the casting was funded. Arnold’s 1921 Dancer was also brass and was cast at H. Noack in Friedenau neighborhood in Berlin so it is possible this would have been cast at the same foundry, though without a mark, we just don’t know. This piece is currently in a private collection.

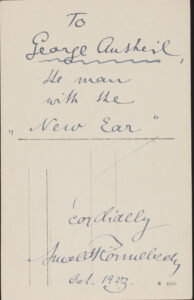

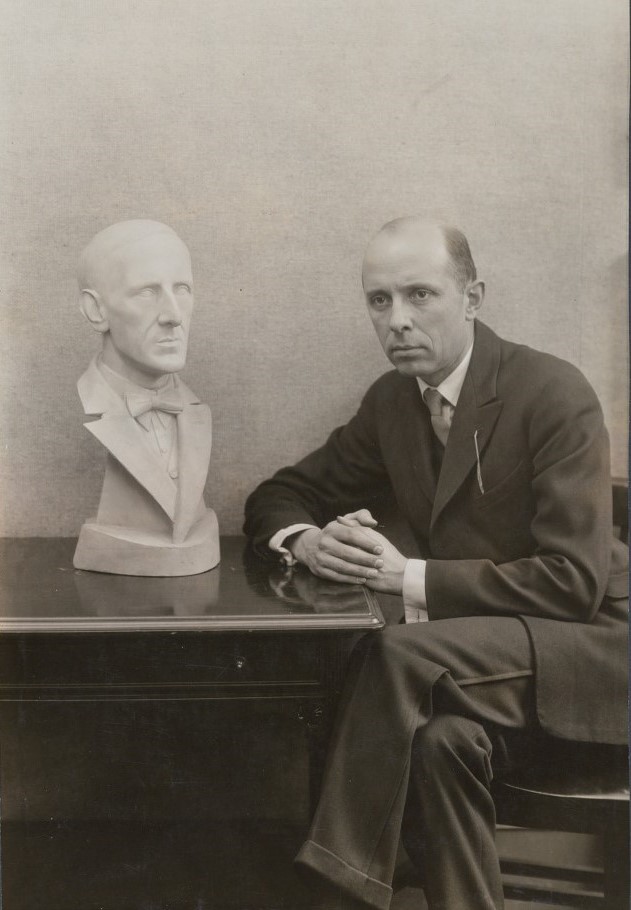

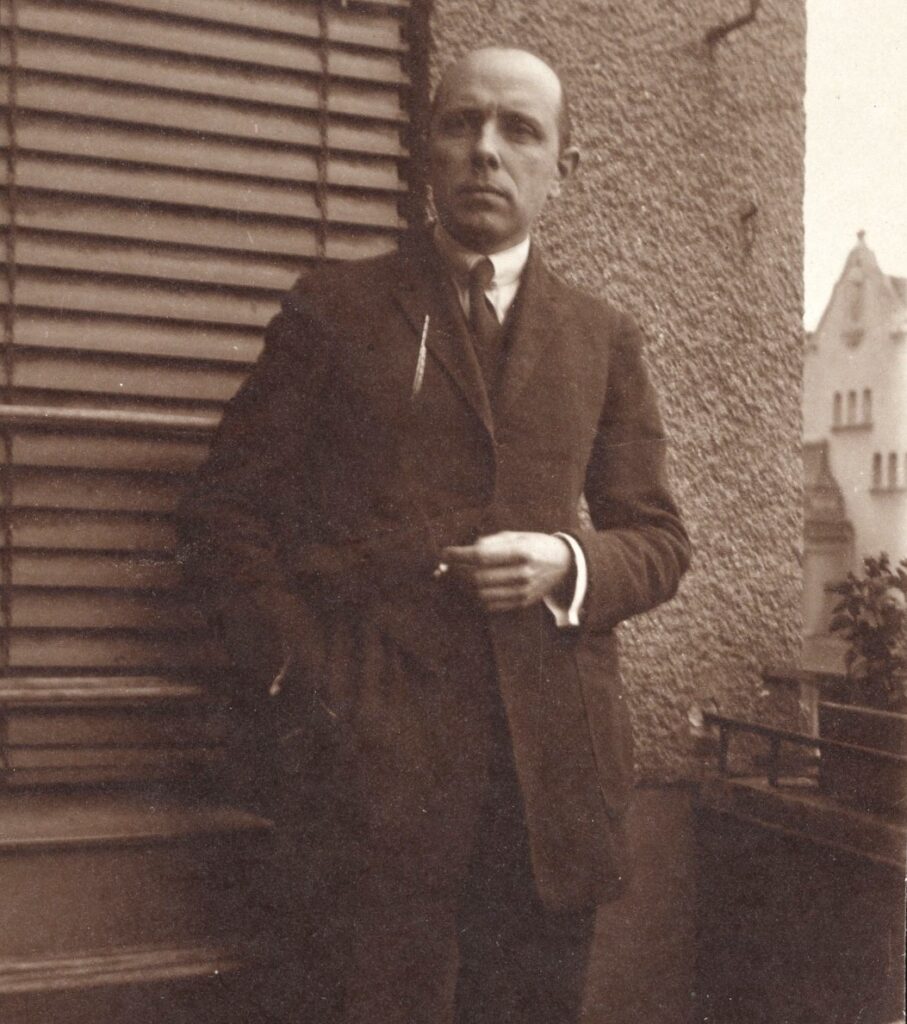

A more traditional portrait executed by Arnold in Berlin during this period was one of avant-garde American composer, George Antheil (1900-1959). Antheil arrived in Berlin in 1922, remaining there until moving to Paris in June 1923. We haven’t been able to find out much or really anything about their meeting or any sittings. Our assumption is that the creative world in Berlin was a small community and that they likely ran in the same circles. Arnold had a life-long love of music, so he would have been intrigued by the young composer. The portrait displays a stylized depiction of Antheil’s then characteristic bangs. After Antheil’s Berlin period, Antheil composed his most well-known work, Ballet Mécanique, in 1924.

Years later, in 1954, Arnold’s portrait of Antheil was on display at the University of Denver theatre when George Antheil’s opera “The Brothers” was performed. Antheil and his wife, Boski, attended the performance. This work was also included in Arnold’s 1925 Weyhe Gallery show in New York. It is currently in a private collection.

Arnold’s travel to the U.S. was originally scheduled for some time in 1922, but the voyage was cancelled due to the death of his fiancée, Alice Miriam. He finally set sail on November 10, 1923 on the S.S. Mongolia from Hamburg, Germany arriving in New York on November 23, 1923. According to the arrival records of the Port of New York, Arnold was in possession of $280, and was neither a polygamist nor anarchist. Good to know. Upon arrival in the US, he stayed with Alice Miriam’s parents, Reverend Pearse Pinch and Mary Pinch in Glendale, Maryland, about 15 miles from Washington, DC. He remained in Maryland and DC area until he moved to Greenwich Village, New York, around October 1924.

In some ways he was similar to other immigrants, departing a place of economic, social, professional and personal challenges and arriving in the U.S. seeking a new life. However, Arnold had many advantages the others did not. He spoke English fluently. Upon his arrival he had a friendly and inexpensive, perhaps even free, place to stay with the Pinch family. He had an established relationship with Alfred Stieglitz which had begun in 1912, which would prove to be an important entry into the New York art world. He had friendships with many Americans he had met in Europe, such as Hartley, Charles Demuth, and Mabel Dodge.

He brought a small amount of his work with him on this new adventure in the U.S. He was not sure if his stay would be permanent, so he left much of his work and his possessions in his Berlin studio. By 1929 he was well established in Denver, held the position of Art Director of the Denver Art Museum, was married and the father of two children, so it was clear that he was going to stay in the U.S permanently. In the summer of 1929 he and Louise visited his family in Berlin, and upon their return brought his possessions to the U.S.

With his move to New York, 1924 would be an exciting and busy year for Arnold. Everything was new and his enthusiasm for his adopted country would come through in his first work inspired by his American experience.

1922

Arnold was extremely productive artistically in 1921 and in 1923, so we are assuming 1922 was no different. We say assuming because the truth is we don’t currently have much information, photos, or records of work produced in 1922. Perhaps it was a period of transition. We think he was supporting himself executing portrait sculptures of German nobility and society people.

Both he and Germany were still recovering from the effects of the war. The mark was devalued, and the dollar was doing well. Consequently, Berlin was full of Americans. Arnold maintained friendships with many Americans that he had met in Paris prior to the war, some of which were currently in Berlin. According to Robert McAlmon in his 1934 memoir of the period, Being Geniuses Together, in 1922 artists and writers such as Hartley, Thelma Wood, Djuna Barnes, Berenice Abbott, dancers Harriet Marsden and Isadora Duncan were all in Berlin. He added, “Rönnebeck, a sculptor, was about”. He wrote of the atmosphere, ”There was an occasional exhibit at the art galleries, but there could hardly have been much incentive to work then, because nobody had money with which to buy, and ‘Auslanders’ passing through were not looking for art”.

Hartley lived in Berlin from November 1921 until October 1923. Another recent arrival was Canadian poet, novelist, translator, Frank Cyril Shaw Davison (1893-1960), whose nom de plume was Pierre Coalfleet. Davison had a letter of introduction to Hartley. Davison stayed in Berlin from Fall of 1922, returning to London February or March 1923. Davison and Ronnebeck met during this time. Arnold would later execute a bronze portrait head of Davison in 1925. They remained close as Davison would serve as the best man/witness at Arnold’s later marriage to Louise Emerson in New York in 1926, but their friendship began in 1922.

One work we are aware of from 1922 is a Portrait Head of Hans Sidow, dated September 1922. Hans Sidow was the father of German poet, writer, Max Sidow (1897-1965), with whom Arnold was friends, as noted in the 1921 post. Arnold and Max began corresponding in 1919 while they both were living in Germany, continuing until at least 1929. The originals of Arnold’s letters to Max and accompanying photographs were graciously given to the estate several years ago. Unfortunately, their contents are currently unknown to at least this Ronnebeck family member, because they are in German and the Sütterlin script, neither of which I can read. Between 1919 and 1922 Max Sidow was studying for a doctorate in art history, producing a thesis on the work of Piero della Francesca. This may explain Sidow’s traveling with Arnold and Theodor Daubler in Italy in 1921. Hans Sidow died in 1923.

While this piece is no longer owned by the Sidow family, it remains in Germany in the possession of a Sidow family friend.

In 1922, Arnold was engaged to American opera singer Alice Miriam (full name Alice Miriam Pinch). They met in Paris around 1910 or 1911, while he was studying sculpture at Académie de la Grande Chaumière with Bourdelle, and she was studying opera privately with Polish tenor Jean de Reszke. They each lived in Montparnasse. In 1914, with the onset of the war, Arnold returned to Germany for military service and Alice relocated to Milan to continue her voice studies. She returned to the U.S. in 1919. In 1920, she toured the U.S. with Enrico Caruso, and living with her sisters in New York City. On July 22, 1922, Alice died of complications of an appendicitis at Flower Hospital in New York. Hartley dedicated his book of poetry entitled Twenty-Five Poems “To Alice Miriam Pinch”, published on January 1, 1923, six months after her death.

Most of the information we have about Arnold and Alice’s relationship is through Hartley’s writings. Hartley wrote about Alice after her death in his autobiography, Somehow a Past, written sporadically in the 1930s and 1940s, but was not published until after his death.

“We were extremely congenial. Alice and Arnold and I – – and it was all set by Alice that when they married, and that too was set – – whoever was successful first – – they would marry. Alice said, “We will take an apartment and you will come to live with us – – and it so seemed it could be that – – for we all loved each other – – we all had work to do and we all were interested in each other’s progress. It was not to be.”

In 1922, Alice was working steadily, including at the Met in the New York, while Arnold was still in Berlin. In May of that year, Hartley wrote to Stieglitz that Arnold has “possibilities in America in six months”. True, there were artistic possibilities, but also personal possibilities – – marriage to Alice. In a January 1943 letter to Hartley’s publisher, Leon Tebbetts (original at the Beinecke), Arnold explained Hartley’s dedication to Alice in Hartley’s 1923 book, and Arnold and Alice’s situation:

“. . . we had decided to get married. Either in our old hunting grounds of superior happiness in Paris or in N.Y. – – the inflation in Germany made any trip to this country impossible, but some American friends of mine bought some of my bronzes, I borrowed some more greenbacks from other war-profiteering friends and bought my passage”.

And then Alice died. Arnold’s move to the U.S. would be delayed by almost a year. When he did finally arrive in November 1923 he lived with Alice’s parents, Reverend Pearse Pinch and Mary Pinch in Glendale, Maryland, until August 1924.

We hope to discover more of Arnold’s work from 1922. Prior to Arnold’s move to the U.S., he was extremely productive in Germany, and we will add that information to this site in 2023.

1921

While Rönnebeck had been studying, working and creating art since childhood and during his art school years (1906-1913), it wasn’t until 1921 that we have examples of a more consistent output. We are aware of a handful of pieces executed prior to World War 1. His Isadora Duncan drawings of 1912, bronze head of Hartley from 1913 and pear wood Crucifixion from 1914 come to mind. There are likely earlier pieces are out there, but they are somewhere in Europe. If anyone has any early Rönnebeck works, please share your photos with us. We would love to see them!

After serving in the German military during World War I, Rönnebeck returned to Berlin and established himself as a portrait sculptor. He had a studio in the Friedenau area at Offenbacher Strasse 3 (building now demolished). His parents lived across town in the Halensee area at Johann-Georg Strasse 20. Beginning in 1913, Hartley was a frequent guest at the Johann-Georg Strasse home, and In November of 1921, he stayed with them for a month. In an undated (possibly 1943) letter to Leon Tebbetts, Rönnebeck wrote, of Hartley and this period:

“ . . . He adored my mother and loved to light her cigarette for her. He had his ‘cozy corner’ on the sofa and he would snuggle into it like a question mark, all curled up with a long cigarett (sic) holder and father would ring for the maid and simply say: ‘that Bordeaux 1920’ and Marsden would curl around the other way and simply exclaim: ‘Wunderbar wunderbar!”.

Hartley moved to his own apartment at 150 Kantstrasse, Berlin, in December of 1921.

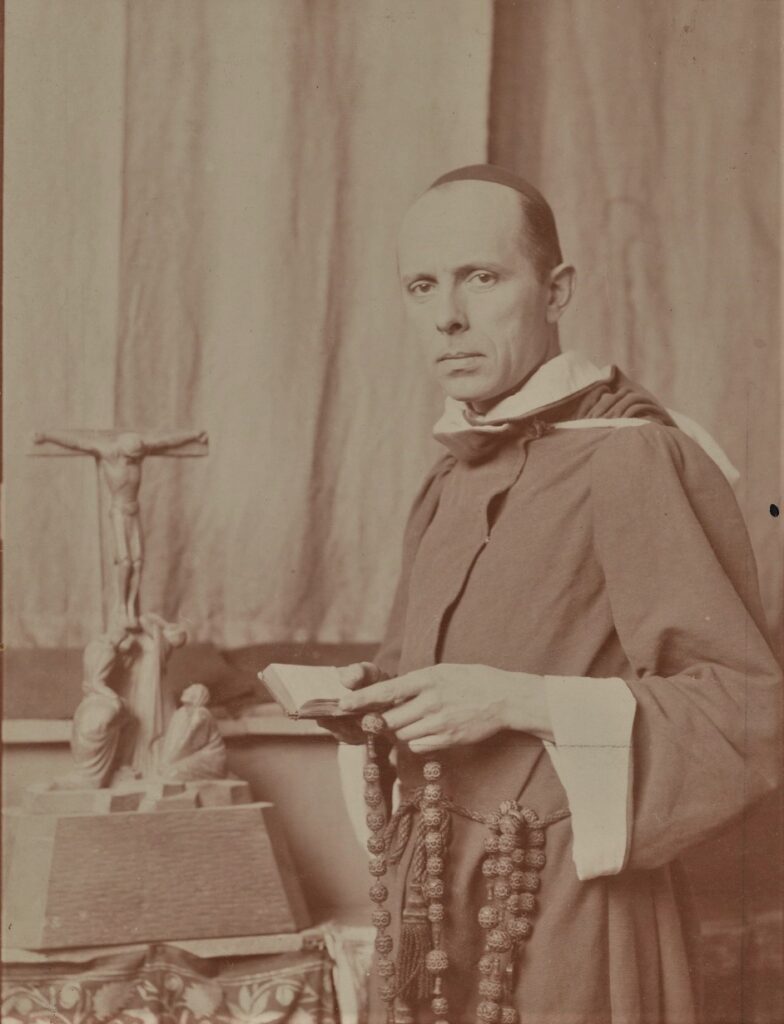

His wartime experience caused him to suffer deeply. He was wounded in October of 1914. His cousin, Carl von Freyburg, was killed the same month. He had seen and experienced some horrific things. To help him recover from the emotional effects of the war, he took an extended trip to Italy. He spent some time at the monastery in Fiesole overlooking Florence, finding it emotionally and spiritually healing, and he briefly contemplated becoming a monk. He affected the wearing of a monk’s robe at two points in his life. First in 1921-1922 (shown left) inspired by his experience at Fiesole. The second, near the end of his life in response to the Second World War. He enjoyed Rome and Florence for its art and history, but did not find it as inspiring as the south. While in southern Italy he executed many pencil drawings of Positano and the Amalfi Coast. He described his experience in a June 1, 1924 interview by Viktor Flambeau at the Washington Herald, entitled Rönnebeck, Expressionist Sculptor, Makes Home in Washington:

“The scenery was like one enormous work of sculpture, houses and rocks seemingly as one. … Nevertheless the lithographs are portraits of the actual landscape, not inventions of the imagination. Here it was. Where Empedocles was born, that I made my first landscape drawings, after which followed a cycle of lithographs”.

This was Rönnebeck’s first foray into lithography, a medium in which he would continue to work and for which he would win awards throughout his career. He created a series of ten lithographs depicting Positano and southern Italy between 1921 and 1922.

While he was newly inspired with printmaking, his preferred medium remained sculpture. Following is a small selection of his sculptural work from 1921:

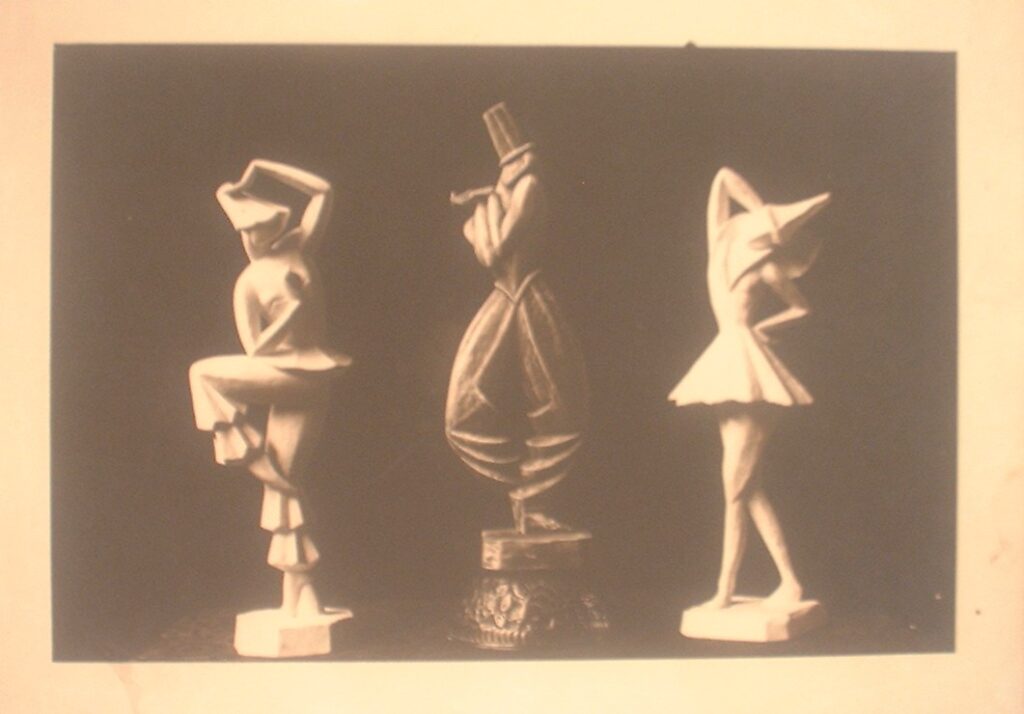

The Dancer, sometimes known as The Harlequin, was executed in 1921 and cast in brass at the H. Noack Foundry in the Friedenau district in Berlin. This piece and others of a similar style had pared down forms with cubist influences. This piece was sometimes described as an “expressionist Pierrot”. We don’t know that much about its creation, but Rönnebeck seemed to be inspired by dance and dancers quite frequently. He executed many drawings and watercolors of Isadora Duncan in 1912, a set of relief panels of nude dancers in 1919, as well as this brass Dancer and several other Dancers in plaster likely in 1921, as well. This brass Dancer must have meant something to him because he brought it with him when he left Germany for the US in November of 1923.

Following are a few notable stops on The Dancer‘s exhibition history:

1925: Weyhe Gallery, New York. In April Rönnebeck had a one-man with show at Weyhe Gallery featuring sixty (60) works. There were 27 sculptures in the show, including three Dancers. In 1926 this exhibition traveled to the Los Angeles, San Diego and Omaha. The brass Dancer was one and we aren’t sure exactly which ones the other two are, but they may be the plaster pieces shown center and right in this undated photo.

1929: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Dancer was shown in the Met’s exhibition “The Architect and Industrial Arts Exhibition of Contemporary American Design” from February 12 to March 24 and continued to September 2, 1929. It was prominently displayed on the mantle in architect Ralph T. Walker’s exhibit, “Man’s Study for a Country House”. In the accompanying exhibition catalog, Walker wrote of the purpose of a room, “In it space elements should be so designed as to engender time elements, through which appreciation can be led from one thought to another, forming a stimulus toward, and an opportunity for, fresh viewpoints, and so encouraging a more continuous period of appreciation”.

Photo at right is by Sigurd Fischer and is in the Library of Congress, item LC-FS13- 308-N4 [P&P].

1934: Century of Progress – Chicago World’s Fair. Rönnebeck was a little frustrated with its inclusion in the fair, as he would have preferred to exhibit something more contemporary. In an April 10, 1934 letter to Robert D. Harshe, Director of the Art Institute of Chicago and curator of the Century of Progress art exhibition, he wrote: “Personally, I regret that a piece of mine of such old vintage has been chosen, a piece which has been exhibited many times before . . . “. In The Dancer’s stead, Rönnebeck proposed his 1932 work Waste, which was a “protest against war”. In his April 13, 1934 response, Harshe gave no reason for the preference of The Dancer over Waste, only saying it “it will not be possible to exchange the group for it”. Perhaps Waste was considered too political. This work is in a private collection.

Other sculptures from 1921:

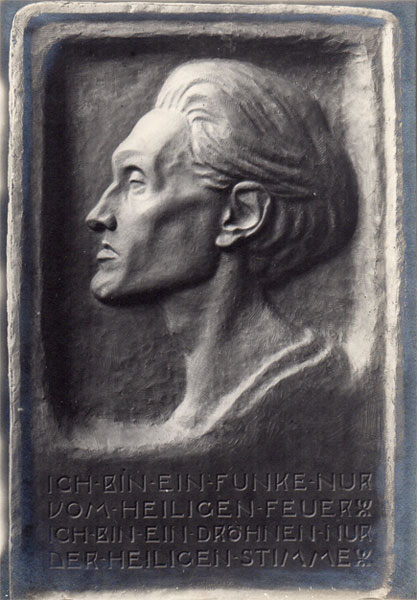

Portrait of Stefan Anton George, plaster. George was a German symbolist poet (1868-1933). Underneath the dramatic profile of George are the words “Ich bin ein Funke nur, vom heiligen-Feuer, Ich bin ein Drohnen nur der heiligen Stimme”. These are the last two lines of from George’s 1908 poem, Entruckung. It roughly translates to: “I am only a spark of the holy fire. I am only a whisper of the holy voice.” In 1909, Arnold Schoenberg was inspired by the poem and used it in the third and fourth movements of his 1909 String Quartet No. 2.

The circumstances of how Rönnebeck received this commission are unknown, but Rönnebeck was acquainted with several other German poets during this period, including Max Sidow (1897-1965) and Theodor Daubler (1876-1934). The location of this work is unknown.

The Combatants is also known as Composition of Rhythmically Arranged Volumes. Shown here in plaster, c1921, it was later cast in bronze at Kunst Foundry in New York, probably 1924 or 1925. Like the Dancer, he brought the plaster version with him from Germany to the US in 1923. It was exhibited in his 1925 Weyhe Gallery show and was part of the selected works that traveled to exhibitions in San Diego, Los Angeles and Omaha in 1926. The bronze is in a private collection.

Poet Theodor Daubler wrote an article about Rönnebeck’s work in the April/May 1921 edition of Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, see below. The article featured reproductions of Rönnebeck’s Head of Max Sidow (date unknown, possibly 1919), Combatants, Hermaphrodite (1919, based on Max Sidow’s poem of the same name), and three plasters of what were sometimes called his “Dancing Grotesques”.

This is a brief overview of just some of the work Arnold Rönnebeck created in 1921. Check back with us in 2022 to find out what was happening in 1922.