This is not a blog, as such, it really just a place where we will post stories, history, anecdotes, photos and information about the career and life of Arnold Rönnebeck.

Update: Isadora Duncan in Paris 1912

As I noted in my previous post about Rönnebeck’s Isadora Duncan drawings, I had not yet corroborated my working theory on how he came to create several watercolors and many sketches of Isadora Duncan in Paris in 1912. My theory was based both on family lore and other reading I had done on the subject. I had thought that while Bourdelle was sketching Isadora for the Théâtre des Champs des Elysées relief panels in 1911 and 1912, his students, including Arnold Rönnebeck, simply sketched alongside him. Seemed logical. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

In November 2019 I had the great pleasure of spending half a day in the archives at the Musée Bourdelle in Paris. There, I read several of Rönnebeck’s letters to Bourdelle, written between May 1920 and June 1923. No answers were found in the letters. Thankfully, however, I had the opportunity to speak with the museum’s archivist and the curator of drawings and paintings. They were both so kind and generous with their time and shared fascinating information with me. I mentioned my theory. They put an end to that idea very quickly. They told me that Isadora NEVER sat (or danced, in her case) for artists. Photographers, yes. Artists, no. Not even for Bourdelle who had executed innumerable sculptures and drawings of her throughout their friendship of 24 years. Bourdelle first saw Isadora dance in 1909 at the Théâtre de la Gaité-Lyrique. He was so inspired by what he saw that the following day he executed 150 drawings of her.

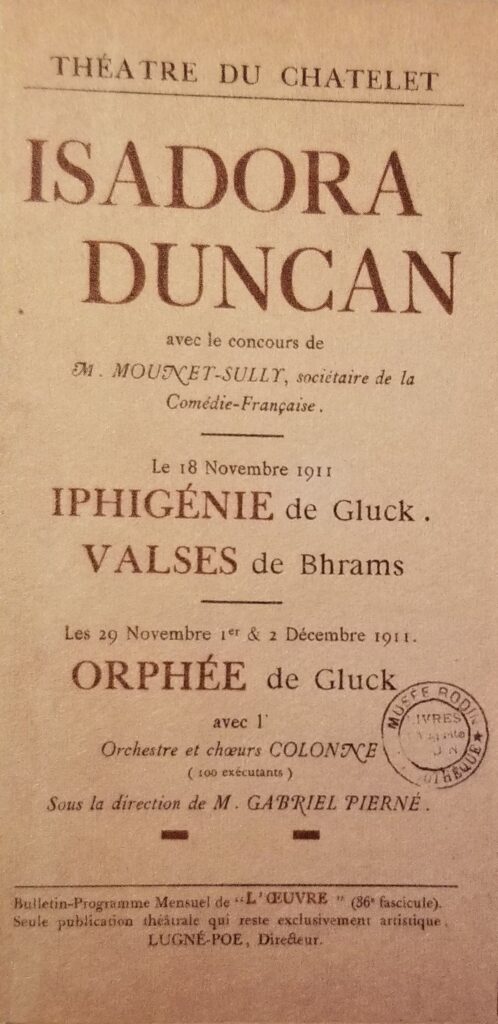

The Musée Bourdelle archivist and curator told me that Bourdelle made all his drawings and sculpture of her from memory after her performances. They said it was likely that Rönnebeck did the same. In November and December of 1911, Isadora performed at the Théâtre du Chatelet on the right bank in Paris. I am guessing that Rönnebeck attended one, if not more, of her performances at that time. Perhaps, like his teacher, Bourdelle, he made the sketches in 1911 immediately following the performance. The watercolors were completed in 1912. Unfortunately I have yet to find any references to Isadora in Rönnebeck’s 1911 journal, so again, I am speculating. I would imagine it would be difficult, if not impossible, to draw and capture her pioneering style without the benefit of seeing her on stage. Since her life was tragically cut short, I am thankful that we have so many artists’ representations of her pioneering style.

If one ever has the opportunity to visit the Musée Bourdelle in Paris, I highly recommend it.

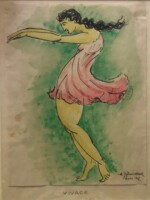

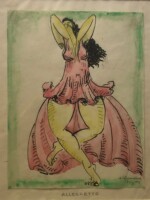

Vivace: Arnold Ronnebeck and Isadora Duncan in Paris 1912

Movement. Paris was all about movement between 1911 and 1913. Well, at least it seemed to be in the Parisian art world. Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase debuted at the March 1912 Salon des Indépendants, the Italian futurists had a landmark exhibition at the Bernheim-Jeune gallery in February 1912, Ballets Russes dance performances were causing riots, and Isadora Duncan’s innovative dance performances were inspiring artists in Paris and around the world.

During this period, Rönnebeck was living on rue Saint Gothard in the Montparnasse neighborhood of Paris while studying sculpture with Émile-Antoine Bourdelle at Académie de la Grande Chaumière. He attended all the local exhibitions, including the Salon d’Autumne, Salon des Indépendants and the futurist show, commenting about all of them in his journal. It was also during 1912 that Rönnebeck developed his friendships with Marsden Hartley, Gertrude Stein and Charles Demuth, but that is a whole other story that has been well-documented elsewhere.

In late 1911, Bourdelle took on the task of creating the exterior decoration for a modern and monumental project being built on Avenue Montaigne in Paris: Le Theatre des Champs-Elysées. The theme of his relief panels was The Meditation of Apollo and the Nine Muses. All of the muses were inspired by the dance and movement of Isadora Duncan. Bourdelle first met Isadora in 1903 at a picnic celebrating Rodin’s investiture as a Commander of the Legion of Honor. He didn’t see her dance until 1909. In order to create the marble relief sculptures for the theatre, Bourdelle made dozens, maybe even hundreds, of sketches of Isadora dancing. In the theatre panel entitled “La Danse”, Isadora is paired with the Ballets Russes dancer and choreographer, Vaslav Nijinsky, whose choreography of the Ballets Russes’s Rites of Spring caused riots after their performance at the Theatre des Champs-Elysées in their inaugural 1913 season.

It was also during 1912 that Rönnebeck sketched, drew and painted Isadora. My (as yet uncorroborated) theory is that Bourdelle’s students sketched Isadora right alongside him. I am still trying to find out more details about this. I am not aware of Rönnebeck turning any of his sketches of her into sculpture. He did, however, turn six drawings of Isadora’s movements into completed ink and watercolor paintings on paper, as shown above. Each is titled using musical terms: Caprizioso, Vivace, Andante, Allegretto, Furioso and Finale. Before completing those watercolors, Rönnebeck, too, made dozens of sketches of Isadora in a variety of dance movements, a small selection of those are shown above, as well.

I think only a few seconds of film exist of Isadora Duncan dancing. Thankfully painters and sculptors, such as Rönnebeck and Bourdelle, have documented her dance, rising to the challenge of translating her dynamic motion into line, paint, ink and marble.

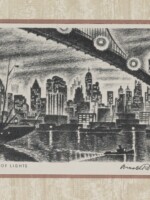

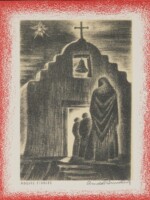

American Artists Group Holiday Cards and Prints

Pictured above are several examples of holiday cards with artwork by Arnold Rönnebeck that were created and sold during the mid-1930s and early 1940s through the American Artists Group (“AAG”). The AAG was a greeting card company founded by Sam Golden in New York in 1934. Their goal was to popularize American art and artists through the reproduction of their work on greeting cards. During this period, artists were struggling along with everyone else. People did not have money to spend on a “luxury” such as art. They could, however, access contemporary American art in an affordable manner through the purchase of AAG’s greeting cards. The card prices ranged from 5 cents to 25 cents each and the customer could order them blank on the inside or with a standard greeting such as “Christmas Greetings and Best Wishes for the New Year”.

Carl Zigrosser, director of the Weyhe Gallery in New York between 1919 and 1940 wanted to take it one step further. During the Depression, in order to help mitigate the loss of sales and income for his roster of artists, Mr. Zigrosser came up with a solution: To publish low price prints in large quantities. Between 1936 and 1938, Weyhe Gallery partnered with AAG to exhibit, distribute and sell and distribute affordable prints, alongside the greeting cards. These prints were produced in significantly larger editions of 2000. They were not signed and each sold for a uniform price of $2.75 each, no matter the artist or image. The prints were made by renowned printer, George C. Miller. Each print came with a hinged window mat with the title of the print and a facsimile of the artist’s signature on the front of the mat. On the reverse of the mat, there was a label identifying the title, artist and authenticity (photo above of the label from Rönnebeck’s Yacht Races). As a price reference, in Weyhe Gallery’s 1936 Fine Print catalog Rönnebeck’s signed limited edition prints were priced at $15-25 each. In September 1936, Weyhe Gallery hosted the first exhibition of the AAG group that included, besides Arnold Rönnebeck, artists such as Paul Cadmus, Howard Cook, Miguel Covarrubias, Mabel Dwight, Wanda Gag, Rockwell Kent, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Louis Lozowick, John Marin, Diego Rivera, amongst many others.

In a KOA radio interview at American Art Week in Denver, Colorado on October 31, 1937, Rönnebeck was asked about how art and artists could be encouraged. He replied, in part, “Those with less means should be told that they can now buy original prints by the best known American artists at a nominal cost. By and by they will come to see how exciting it is to build up a little collection that can be changed around, a collection that they can enjoy instead of saying as I have often heard, ‘I have an old reproduction of a fine oil in my living, but of course I never look at it’. They should look at it! Some of the greatest collections in this country started very humbly because somebody wanted to look at something”.

While the association between AAG and Weyhe Gallery only lasted from 1936 to 1938, Rönnebeck work continued to be featured on AAG cards until at least the holiday season of 1940. During this period, Rönnebeck sold several images on greeting cards and affordable prints, some possibly made specifically for AAG and others from work he had created in the 1920s and early 1930s. Known titles sold through AAG included Adeste Fideles, Red Rock Lake, Smooth Sailing aka Grand Lake, Pageant of Lights aka Manhattan, Adoration and Madonna and Child. There could be more. There is an additional sailing image on a card that I have only seen on this card, so that may have been created solely for AAG. It is pictured above and it was a holiday card for Philip and Jean Roosevelt in 1935 or 1936. Philip Roosevelt was an avid sailor and a first cousin once removed from Teddy Roosevelt. I’ve only seen a small selection of the correspondence between AAG and Arnold Rönnebeck, but I was impressed to see that in the 1938 holiday season, he sold 7480 cards of a “new” 1938 unknown image, 962 of Smooth Sailing and 270 of another unknown image. In 1940, two of Rönnebeck cards were very different from his previous offerings. They were made of foil etched with images based on sculptures he had executed years earlier (Adoration and Madonna & Child, see photos above). These sold for 25 cents each.

All of the above pictured Rönnebeck AAG greeting card originals are in the Arnold Rönnebeck and Louise Emerson Ronnebeck Collection at the Archives of American Art (“AAA”), in Washington, DC. The AAA also holds the archives of the American Artists Group. They have an almost complete set of all of the cards they produced during their first season, in 1935. The collection isn’t digitized, but it would certainly be fun to browse through once we can travel again.

Shangri-La: The Spirit of Hospitality Welcomes the Stranger

In Denver, Colorado, modern architecture, contemporary literature and a Hollywood movie converged in one grand and ambitious project. Modern sculpture was almost included to the mix. In 1938, Harry Huffman, a Denver movie theatre owner, completed construction on a mansion in Denver. It was not your traditional mansion of the American West. Its inspiration came from a little farther east. Okay, a lot farther east – – Tibet. Well, sort of. Its inspiration came from Hollywood’s version of Tibet, as depicted in the 1937 film, Lost Horizon. The home, designed by architect Raymond Harry Ervin, is grand and elegant in the streamline modern style. Huffman and Ervin created a bit of Shangri-La in the Denver hills, with more than a little inspiration from Hollywood.

The film Lost Horizon was directed by Frank Capra and starred Ronald Colman, Jane Wyatt, Edward Everett Horton, H.B. Warner and Sam Jaffe. The sets were designed by art director, Stephen Goossen, who was a trained architect before he became an art director. He won an Oscar for his design work on the film. Huffman was no stranger to looking abroad for building inspiration. One of his Denver theatres, the Aladdin (demolished in the 1980s), was modeled after the Taj Mahal.

Arnold Rönnebeck met with Mr. Huffman in August or September of 1938 and subsequently produced several sketches of proposed sculptures for the grounds of Denver’s Shangri-La. As far as I am aware, none of the pieces were executed. In the archives. I have found only one page of a September 13, 1938 letter from Rönnebeck to Harry Huffman discussing this potential project and it sheds little light the subject. In it, Rönnebeck writes that he wants to “help round out the spirit expressed in Shangri-La and its mysterious background, ‘Lost Horizon’. You encouraged me to put such ideas on paper, in the form of sketches. This I have done.”

The first drawing shows the front of the home, with the proposed sculpture, Spirit of Hospitality, positioned near the entrance. In the 1933 novel, while recounting to Robert Conway the story of how Father Perrault arrived at Shangri-La, the High Lama says, “There, to his joy and surprise, he found a friendly and prosperous population who made haste to display what I have always regarded as our oldest tradition – – that of hospitality to strangers”. In the second panel, on the left we have a detail sketch of the Spirit of Hospitality. In this sculpture, the hands are significant. The Buddha’s right hand is in the “Karana mudra” position. This powerful gesture expels negative energy. Perfect for the entry of a home.

On the right, The High Lama. The High Lama is the closest connection to the film with its depiction of Sam Jaffe, the actor who played the High Lama in the film. This sculpture was to be on the reverse of the Birth of Buddha fountain, seen in third drawing. The fourth sketch depicts a seated Buddha sculpture by of a pond and waterfall. In this Buddha, the hand positions symbolize the earth as the witness to his enlightenment.

Rönnebeck’s oil painting, White Lotus of Lhasa, c1941, would seem to be inspired by either or both of the novel and film as well. The painting shows the Buddhist hand gesture signifying the expulsion of negative energy, the same one he depicted in the Spirit of Hospitality sketch. The lotus flower symbolizes enlightenment, purity, devotion or rebirth.

Given the state of the world in the 1930s and 1940s, everyone was looking for their own Shangri-La, be it in Tibet, Hollywood, Denver, or even Maryland. In 1938, the WPA completed construction on a presidential retreat in Maryland. In 1942, President Roosevelt named the retreat Shangri-La. In 1953, President Eisenhower renamed it Camp David. I prefer Shangri-La. Throughout his life, Rönnebeck was on a spiritual quest. This quest influenced his work in different ways over the years. Perhaps his participation in this project was, in a small part, a continuation of that quest.